Ad Astra

Our Destiny Takes Us Far Away

In which I lay out arguments for the exploration and colonization of the cosmos as a civilizational project.

It’s easy as a human being (even one in the hyperreal, endlessly abstracted modern world) to forget most of reality: the observable universe. One casual estimate puts our solar system at 0.00000000000000000000000000000000000000829% of the observable universe, which is certainly not all of the universe (indeed, the entire universe is probably at least 200x larger than the spacetime bubble which we can theoretically observe, and might well be infinite).

What exactly is the purpose of all of this, this vast 3-dimensional landscape of matter and energy? Obviously science doesn’t think in terms of ‘purpose’ (at least not consciously) but humans do. It seems that individuals today are barely more sophisticated than the medieval star-gazers who believed that the world was a divinely-ordered stage, set under perfect crystalline spheres. We certainly know that there’s a lot more out there, but when we discuss the nature of evil or the possibility of God or the arc of history we seem to fall back into the comfortable and fallacious habit of thought: our world is a major and important setting within the cosmological whole.

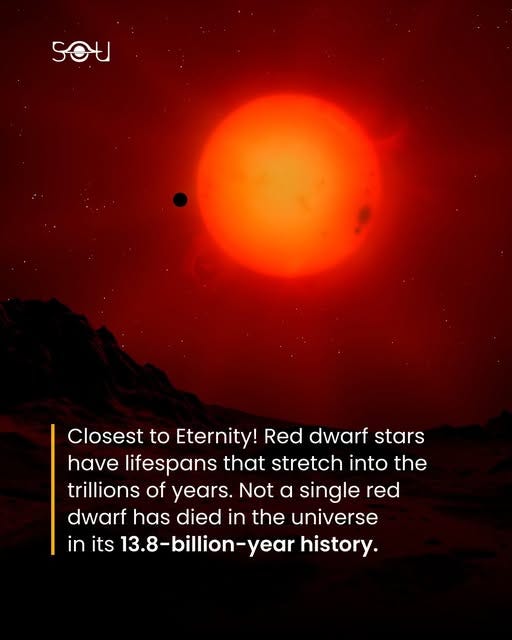

I think that contemplating the spatial enormity of the cosmos and the grand sweep of time (for example, many red dwarf stars are projected to survive for trillions of years - our universe seems to have existed for 13.8 billion years) has implications for our notion of God and our conceptualization of evil and pain and the purpose and destiny of our species.

Regarding God, I think we must dispense with the idea of a personal world-spirit, a creator with thoughts and emotions and desires that could be comprehensible to humans. TON 618 is a black hole that appears to have a mass approximately 66 billion times that of the sun. There are quasars we have observed with temperatures of over 18 trillion degrees Fahrenheit. Pulsar PSR J1748−2446ad is about 30 kilometers in diameter, but due to its incredible mass and energy it rotates 716 times per second, meaning that its surface is moving at 24% of the speed of light. The galaxy Porphyrion contains cosmic jets (super-energized, violent discharges of gas and subatomic particles) which are over 23 million years long. That means that the origin of the jets (a supermassive black hole digesting objects and flinging mass and energy outwards from its accretion disc) is so awesomely powerful that it is launching matter and energy a distance which is around 1,500,000,000,000 times the average distance between the Earth and the sun. So, if there is a being who created and oversees and controls all of this, such a being cannot be comprehensible to us. We might behave as if He (it) is, but He/it simply cannot be. And the idea that this being arranged reality around us - around our species and its past and future - seems completely nonsensical. Even the Bible were broadly accurate, surely there’s a lot more going on.

“Embrace this moment. Remember: we are eternal. All this pain is an illusion.” - Tool

A similar logic could be used in considering the ancient question of theodicy, the philosophical problem of explaining why pain and sin exists in a world alongside a benevolent creator. It’s not exactly a neat resolution (if such a thing was available it would have been proposed 3,000 years ago), but consider this: the pain and trouble and violence and loss that we experience today seems poignant and tragic. After 20 years the ache has faded, somewhat. After 100 years the loss has probably been forgotten, swept away by the onrushing tide of cosmological time and change. After 5,000 years the loss has almost certainly been swept out of existence. Perhaps it is the merest echo of some memory (if it has historical weight) but the suffering is gone. So pain and loss and sin are purely effects of consciousness. If a consciousness could apprehend the full sweep of time, if it could understand the path of every photon before it reached the eye and could look ahead and see the multivariate branching decision tree as the vast engine of entropy slowly, slowly ground towards chaos, then there would be no suffering. There would be no sense of loss. Suffering and loss are simply consequences of our limited perspective and the biological shackles of emotion and connection. There is a reason that wise people seem serene, non-reactive. Dial that kind of wisdom up by a magnitude of 100 and imagine, if you can try, how such a being might see the world. That is the cosmic perspective, which until now we have almost completely ignored. Despite having the technology (or nearly having it) we remain comfortable on our little globe, ‘planetary chauvinists’ as Carl Sagan put it. We need a collective project, for the health of the individual and for the health of our civilization and for the health of the species. We always have even if that was just maximizing output in the next hunt. As project after project has been fulfilled, we’ve become decadent and distracted. Without some external pull I doubt we’ll be able to pull ourselves out of it.

Imagine your life, its past and future. Now factor in the vast scale of the universe - the 93 billion light years of expanding diameter which encompasses just that part of the universe whose light could, conceivably reach us (light travelling for 13.8 billion years, but stretching out over a spatial expanse which has been expanding at an accelerating rate for billions of years).

This is reality, at least the layer and scale that our senses are able to perceive. Our planet feels like home, and it is, but if we restrict ourselves to habitation and travel on the surface of the globe, we will be shirking a kind of cosmic duty. As far as we know we are the only analytical, creative, narrative intelligence in the universe. That gift and that burden compels us to go out and explore, eventually. So that is argument #1 for space exploration and colonization:

(1) Space travel is necessary to understand the whole of reality, or at least the parts which we have access to. To apprehend the nature of time, change & entropy, consciousness, God, suffering, and reality itself we must access the cosmos.

Our sun (Sol) is gradually brightening, as the core increasingly fuses hydrogen into helium. It’s already about 30% hotter than the period after its formation. Within 500 million years the Earth will be 25-30 degrees F hotter, on average (due to a 5% increase in solar luminosity), regardless of any other terrestrial changes. It’s possible that the heating will cause CO2 to release from rocks, or methane from permafrost and other surface geologic features, which will cause a runaway greenhouse effect. But even if that doesn’t happen, our oceans will have boiled away within 600 or 700 million years. All life on Earth will end soon (in geologic time scales) after that.

Then there are all of the more random and pedestrian risks of being a denizen nested in physical reality: asteroids, solar flares, supernovae, orbital interferences, axis shifts, super volcanoes, etc.

Our universe is not a hospitable place. Anyone who posits a creator God must at least attempt to explain not only the vast and (so far) mostly lifeless expanse of the cosmos - with its unimaginable distances and energies - but also the trillions of worlds that have been sterilized or vaporized by accretion disks and asteroid impacts and solar expansion events. As C.S. Lewis wrote:

We have two bits of evidence about the Somebody [behind the Moral Law]. One is the universe He has made. If we used that as our only clue, then I think we should have to conclude that He was a great artist (for the universe is a very beautiful place), but also that He is quite merciless and no friend to man (for the universe is a very dangerous and terrifying place).

So that is argument #2 for space exploration and colonization (our cosmological exodus):

(2) Space travel is necessary to preserve intelligence and protect at least some of our progeny from inevitable catastrophe.

Many modern people take a cynical view of legacy, the future, and even our civilization (its technological developments and its values and its history). This is pure affectation and posturing. No one really believes such things. If you were so repulsed by civilization, you would leave it. If technology disturbed you so much, you’d disengage. If appeals to the future of our species are met with ‘so what?’ or ‘why should I care?’ then I would ask those people: why do you love your mother? Some things are simply biologically encoded within us (the most important things, generally) and are neither accessible or alterable by logic or argument. They form the basic telos of human life. It’s nice (in a way) that we’ve reached a point at which confused and alienated modern people can pretend that these things don’t speak to them, but anyone who tells you that they are ambivalent to the extinction of humanity is either (1) lying (which is by far the most likely account) or (2) so twisted and bitter that they should be considered dangerously mentally ill. Surely some people are so strange or wounded that they could see the world perish without upset, but these are deeply damaged people and they should have no input into local elections or schoolboard meetings, much less discussions about the destiny of human space travel.

While we’re near the subject, our current, wholly artificial approach of scientific neutrality and cosmological noninterference strikes me as completely inappropriate, reflective of a 20th century attitude which is squeamish about death and growth and competition and power (squeamish about nature, in other words, and regarding humans as somehow apart from it).

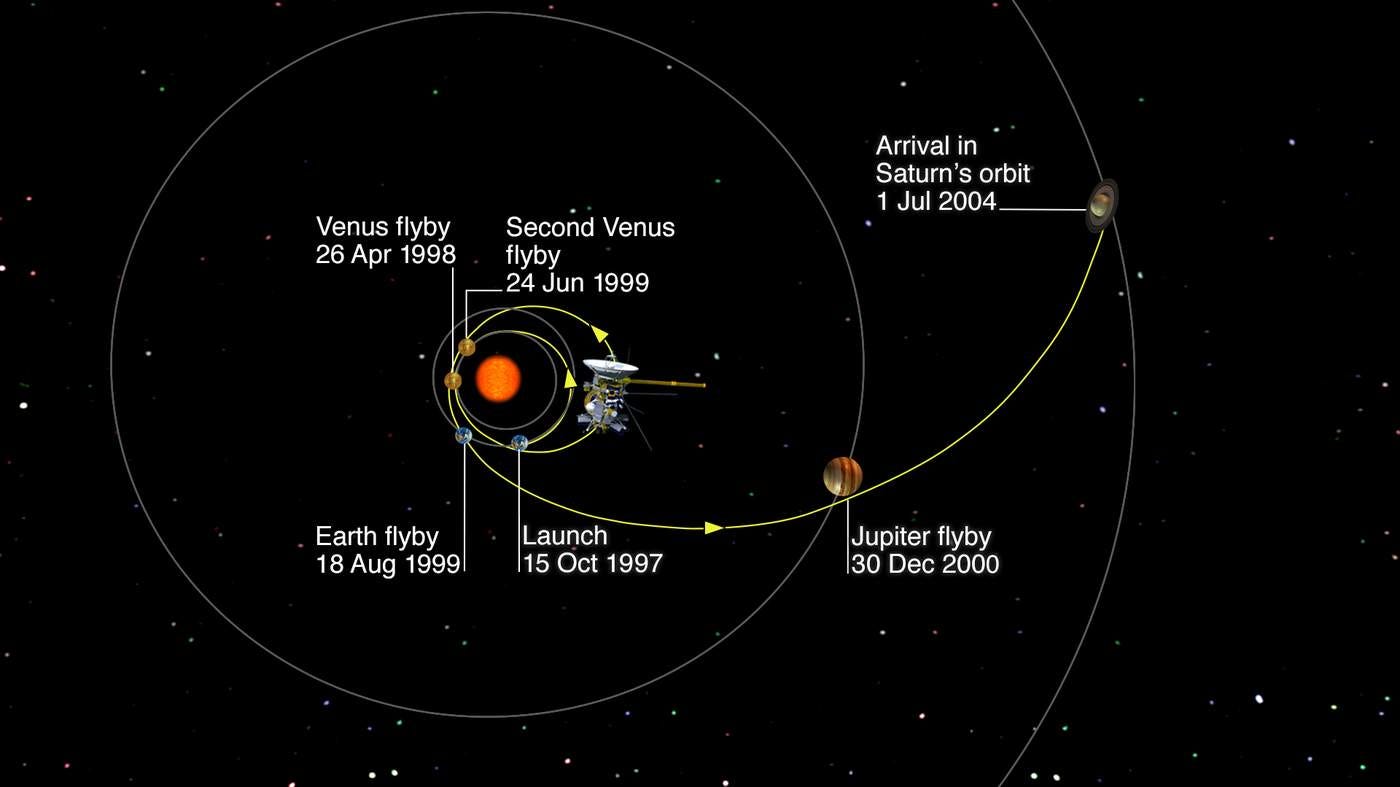

I’ll give you an example: when the Cassini probe began losing power and experiencing gravitational decay in 2017 (after visiting Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, and some of her larger moons in orbits and flybys) the craft was intentionally directed into Saturn’s atmosphere, where it would disintegrate in the progressively thickening clouds of ammonium hydrosulfide. This was done so that Cassini wouldn’t ‘contaminate’ any of the Saturnian moons with earth life. Why are we not spreading life as far and wide as we can? We’re not judicious and neutral observers, trying to preserve a neat shadowbox display. We’re animals, trying to survive, who recognize the value of life and sentience. What if there is a native biome on Europa or Titan or Mars? Our microbes will compete with and perhaps hybridize and improve the local fauna… or they will not. The worst case scenario is that our microbes wipe out the native species, and replace them with forms which are (almost by definition) superior. In the struggle, only improvement can result. And what if a world that was lifeless reluctantly welcomes our planted seeds… and in 400 million years hosts complex life, even intelligence? This is the same conceit that pushes biologists and policymakers to ‘conserve’ species and ecological niches on Earth. I understand the impulse - there’s a kind of sadness in the final vanishing of a form of life. But that’s what nature is. It’s all one big charnel house in the long run. If extinct species left ghosts, our planet would be packed with them. There is no preservation or conservation or stability in nature on medium to long timescales. We should stop behaving as if there is. We should seed the universe.

Contrary to popular opinion, a dangerous and expensive space race is very likely necessary for a happier and prosperous Terran (earthbound) society as well. This might seem counterintuitive, so I will explain.

Before and during the space race in the 1960’s there was a popular outcry about the waste of resources. We have poor people and sick people, after all! What about the poor?

A rat done bit my sister Nell

With whitey on the moon

Her face and arms began to swell

And whitey’s on the moon

I can’t pay no doctor bills

But whitey’s on the moon

Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still

While whitey’s on the moon

The man just upped my rent last night

‘Cause whitey’s on the moon

-Gil Scott-Heron

As far as I know the Apollo missions didn’t raise anyone’s rent. After decades of subsidized housing and exorbitant medical costs - while urban decay continues to deepen and people get fatter and unhealthier than ever - we know that handing out large sums of money for these kinds of purposes has perverse and unintended effects. More money for housing can lead to less and worse housing. More money for medicine can lead to more sloth and disease. More money towards poverty can create an awful learned helplessness, ruining the lives and futures of millions relative to what they otherwise might have been.

The entirety of the Apollo Project cost (according to Grok) $25.4 billion. In 2024, we spent about $100 billion on food assistance alone. If our progressive elite had their way (increased immigration, with increased and unconditional food assistance for all of them) this could easily have doubled, or tripled. It still could. If current trendlines persist, it probably will in my lifetime. And that’s only food (much of it junk and snacks) we’re discussing, in the fattest and most sedentary and best fed country on Earth. The sad and counterintuitive fact is that providing people with easy material assistance (aside from some acute and rare cases) doesn’t seem to help them. It seems to do the opposite. Just as making conditions difficult for people and prompting them to work for things often improves those people, making things easier and excusing them from work seems to soften and enfeeble them.

Africa has received at least $1 trillion in foreign aid in the last 20 years. That’s about $2,300 for every poor man, woman, and child on the continent. That should be more than enough to lift all of them out of poverty. Forget corruption and distribution issues and human capital and capacity building needs and incentives and business culture - how much money does Africa need to resolve poverty? The plain answer is: an infinite amount. Every Western country could literally bankrupt itself, pouring wealth into the DRC and Senegal and Algeria and Mozambique… and there would be a fabulously wealthy nouveau riche class in the cities (talking about social justice, no doubt) and some kind of enriched middle and professional class around Abidjan and Dakar and Johannesburg and Nairobi and Kinshasa, with the reliable hordes of rural and urban poor scattered around them. There would be poorly maintained server farms and ghostly, half-completed apartment blocks and poorly constructed civil engineering projects (a lovely opportunity for graft), and little else.

An aside regarding foreign aid: When I was in Afghanistan (after more than a decade of U.S.-NATO ‘development’ grants and ISAF joint projects and lucrative contracts) I saw multiple ‘police’ and ‘army’ facilities, built to house thousands of recruits and trainees and volunteers. They had mess halls, fully equipped gyms, guard towers… and they sat empty, aside from skeleton crews of US army regulars or (more often) contractors. The construction of these facilities netted companies like KBR and Halliburton and Raytheon many millions of dollars, but the benefits didn’t accrue to the Afghans (and certainly not to the American taxpayers from whom the money was taken). Foreign aid is often like this. If you want to help poor people, give them small amounts of food or money, conditionally. Give them basic infrastructure. Anything beyond this - any big projects or complicated grant programs or public awareness campaigns - will be constituted to redirect money from taxpayers to Western consultants and nonprofits and researchers and bureaucrats, with a large share getting siphoned off in local or national corruption. This has been understood for more than 50 years, and it is suspicious when professionals who work in this world pretend as if they don’t already know it, as happened in the wake of the cuts to USAID.

A society does not get rich on handouts and charity. It cannot. It has never happened and it will never happen. So the argument that we have poverty and human needs and social problems on Earth shouldn’t deter us from cosmic expansion. We always will have them, and mostly they’re results of other, deeper failings: broken cultures, flaws and vices, or areas with high concentrations of greedy or stupid or psychopathic individuals None of this situations can or will be solved by cash infusions.

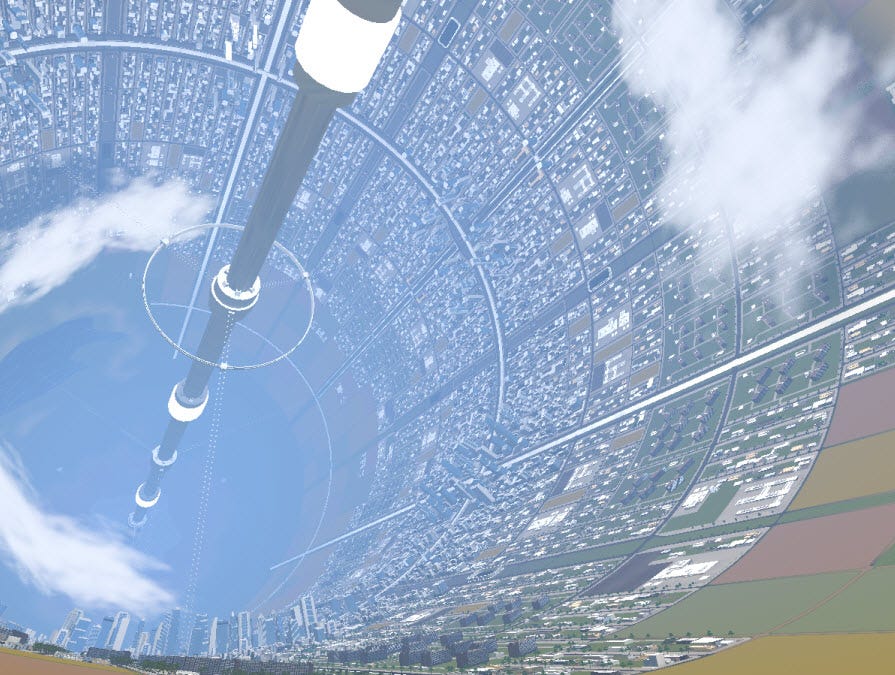

The potential financial and technological benefits from exploring space are enormous, of course. Inner solar system asteroids rich with heavy metals, Helium-3 lying rich for the harvest in the atmospheres of Saturn and Neptune (and even some on the surface of the Moon), platinum and iridium in the Kuyper Belt - all of these resources and more are out there, waiting to be gathered and used. The engineering and technological advances we will gain from building intersolar probes, O’Neill cylinders, Lunar launch depots, and subsurface Martian colonies cannot be overstated.

However, the real benefits to space exploration will be to offer a spiritual and existential dimension to life, one which has been missing since the age of exploration came to an end. Our societies have generally been structured similarly: there is a home area, and then there are warriors and explorers and traders and colonists who venture out, against great risk, to win rewards. These individuals have nearly all been men, and they are driven by money and status and honor (which are all proxies for sexual access to women). As John Carter writes:

If you want your society to produce transcendent excellence in a given field, the only way to do so is to attach a competitive male status hierarchy to it. With status on the line, men will throw themselves into the arena, immersing themselves completely, devoting their every waking moment to mastering a skill or subject, making it their life’s purpose to push a discipline beyond its limits. Competitive pressures between the best of the best then raises performance to its apogee. Iron sharpens iron.

Nearly all of our earthbound hierarchies have been diluted and weakened, by female integration and by bureaucracy and by safetyism (which might all be three aspects of the same trend). The militaries of every Western nation, police and fire departments, large technology companies, entertainment companies (Hollywood and streaming services and publishing) have all seen a dramatic shift in their cultures and outputs over the past 50 years. It is not an exaggeration to say that the benefits are now significantly reduced and the organization risks significantly increased for a masculine man planning to enter any of these fields. The organizational cultures, the sense of mission and focus, the imposition of strict rules and standards (for everything from physical aptitude tests to book awards to promotions) have melted away, replaced by indulgent and shifting metrics which focus on reassuring and ‘supporting’ the individual, or empowering certain groups. All of these examples and more are now burdened by thousands of fairly unproductive earners and pension-getters, who are less active than were historical participants, more likely to sue, more focused on feelings of safety and propriety, and who feel entitled to remake society itself according to their wishes… one workplace at a time.

Space will not only open up a frontier where such concerns will melt away (in the face of danger and the necessity of high performance, any focus on safety or feeling supported should seem spurious, as it always is) but it will create a landscape - physical and psychic - for adventurous and obsessive and high-caliber people to ply their trades and develop their skills. Women will be among them, of course, but only those with the highest risk appetites and the strongest senses of duty, which is the way it always should have been, even for the institutions I mentioned. Most women seem temperamentally unsuited to be engineers, for example, and more men seem to gravitate towards the fields and have the skills to excel there. If women enter that field then it should be with the understanding that they are a rare and happy minority, and there’s nothing wrong or unnatural about that. Unfortunately, women who enter professional spaces sometimes begin advocating for more ‘representation’, more opportunity, more concessions, more cultural attention. They do this using social sympathy and bureaucratic avenues and a natural male urge to placate and support them, and they have cumulatively remade society through these routes. Those malcontents might represent a minority of the female participants, but the majority never seems to resist or obstruct them, and the modern managerial system’s incentives are to promote women and expand their participation as much as possible, even in jobs where they are usually fundamentally unsuited. Space will offer a contrast to that, and by creating a contrast it will led an implicit critique of the way we’re currently doing things. There are many factors behind organizational dysfunction in the 21st-century, but this isn’t the least among them. Space will be a virgin realm, where the demands and the requirements for great sacrifice will create a natural mechanism for reasserting the sexual labor roles which persisted from ca. 1 million BCE until approximately 1975 ACE.

Space will also reawaken our sense of the vast mystery of reality and the danger and the tragic brevity of life (which is the quality that makes it beautiful, for us). It will reconnect us with the fundamental and majestic inscrutability of the universe we inhabit, in a daily and active way which is unimaginable right now. It will reenchant the minds of Western man, to some extent, and it will give us a new sense of optimism and possibility. It will also instill a vanishing quality: grit. The crucial importance of being able to suffer through great privations and remain committed and determined is certainly not something which is taught in schools or workplaces or communities in the modern world any longer. It’s always been an elite value, even when it was the norm for men, because it is a very difficult ideal to measure up to. We have progressively erased its consideration from our culture (it makes those who are soft feel badly about themselves, and its completely incomprehensible to the Longhouse, which cares only that people be nice and conform socially and reflect bureaucratic narratives back at it). Grit will return with the venturing into space. So that is argument #3 and #4 for cosmic exploration:

(3) Space travel will make us a leaner, healthier, richer and more advanced civilization. It will benefit us (even the poor among us) more than any expansion of transfer programs and entitlement spending.

A digital imagining of an O’Neill Cylinder, a, artificial, rotating space habitat whose spin creates endogenous internal gravity.

(4) Space travel will re-awaken our sense of the mystery of reality. It will re-assert sensible, historically-grounded sex roles, provide incentives and rewards for outstanding individuals to do socially useful things, and reacquaint us with the values of toughness and sacrifice and competence.

Those values are currently fading away, some quickly and some slowly. We should not wait until they’re gone.

You’ve identified something real here: the loss of meaning, the drift, the way comfort and bureaucracy can hollow out purpose. And the cosmic scale you invoke does shatter comfortable anthropocentrism.

But I wonder if the solution you’re proposing carries the same pattern as the problem you’re diagnosing. Competitive hierarchies, extraction, dominance, the frontier as escape valve—these are precisely the dynamics that created the civilisational malaise you’re describing. Extending them into space isn’t transformation; it’s elaboration on a grander stage.

The question isn’t whether humanity should engage with the cosmos. It’s whether we can do so as something other than what we currently are: adolescents seeking new territory because we’ve fouled the old one, rather than adults who’ve learned to participate in living systems without consuming them.

Space won’t save us from ourselves. We’ll bring ourselves along.

At 84, having spent decades in systems thinking and complexity science, I’ve come to suspect that maturation—not expansion—is what’s actually required. The frontier we need to explore is internal, not interstellar.

Wow! Great writing, James! Have you seen the film Ad Astra? I thought it was alright, it looked stunning and did a slightly better job of selling Space Travel than The Martian or Interstellar. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6AaSMfXHbA