Masculinity in Revolt

The Nietzschean Themes of Fight Club (1999)

This is precisely the risk modern man runs: he may wake up one day to find that he has missed half his life.

-Carl Jung

Masculinity is not something given to you, but something you gain. And you gain it by winning small battles with honor.

-Norman Mailer

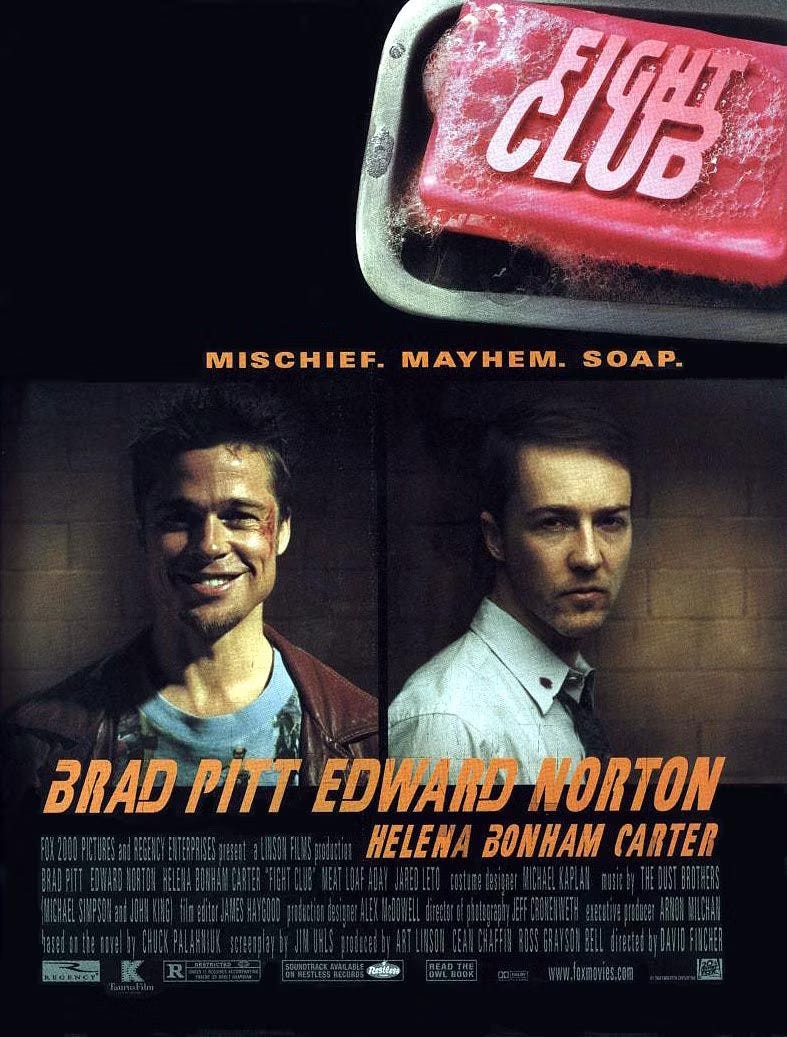

If you haven’t seen Fight Club (1999) then you were probably not a young man during the 1980’s or 1990’s. While it did poorly in theatres it has since become a classic of 90’s cinema and is one of the most piercing and layered explorations of modernity and masculinity and the effects of consumer culture.

Plot

The main character remains unnamed. In the script he is just called ‘the narrator’. He’s a field investigator for a major car company who travels around the country, viewing accident sites and the burned and crushed bodies of crashed cars in order to estimate whether a recall would be profitable or unprofitable for his employer. With this setup the story has introduced several trenchant elements: the ultimate driver of profit, the shallow and standardized experience of business hotels and commercial flights and layovers-a blur of near-identical motel flight terminals and baggage claims and reception desks-and the dull conformity of modern office work.

The narrator seems to be a reliable employee and he works to satisfy the “Ikea nesting urge,” the drive to acquire enough clothes and culinary items and pieces of home furniture to feel complete and validated. “I would flip through catalogues and wonder ‘what kind of dining set defines me as a person?’” His life lacks friendship, love, adventure, struggle, suffering.

He is desperately unhappy but unwilling to admit this even to himself, and he develops terrible insomnia. “For six months I couldn’t sleep… When you have insomnia everything is a copy of a copy of a copy.” He visits a doctor, seeking drugs to relieve his condition (“blue tuinals, lipstick-red seconals”) but the doctor refuses, pointing him to valerian root and exercise. “You need healthy, natural sleep” he tells him. When the narrator pleads that he is in pain the doctor dismisses his plea, telling him that if he wants to see pain he should visit the testicular cancer support group. Lacking any hobbies or friendships or purpose the narrator goes, and is confronted with the reality of suffering, which has been completely absent from his life. He hears men commiserating about their ex-wives having children… with their new husbands. He meets a body builder (Bob, played by Meat Loaf) with terrible gynecomastia, a product of hormonal imbalances caused by a lifetime of steroid abuse and the attendant cancer. They break off into ‘one-on-ones’ and Bob opens up to the narrator, weeping… and then the narrator breaks down. He begins weeping, finding release in being confronted with the suffering of others. He has found a cure for his insomnia. “Babies don’t sleep this well.”

“I became… addicted”

Unfortunately his narcotizing and cynical haunting of support groups is interrupted by an interloper, a living embodiment of the chaotic feminine element, Marla Singer. She’s poor, impulsive, confident, uninhibited, bizarre, intelligent, and unconventional. “Marla’s philosophy was that she could die at any moment. The tragedy, according to Marla, was that she didn’t.” She was a ‘tourist’ and the lie of her presence reveals the lie of his and once again he can’t cry, so he can’t sleep.

It’s around now that Tyler Durden (Bradd Pitt) enters the story. It bears keeping in mind that the smart-even philosophical-dialogue and dark, mundane cinematography and fast-paced, episodic pacing of the film has, until now, effectively distracted the audience from the strange gaps and inconsistencies in the plot, which only become fully realized later. The narrator meets Tyler on a flight and is quite taken with his indifferent and assertive masculinity. Tyler is a kind of incarnated dream for restless young men: he steals what he wants, he does what he wants, he says what he wants, and yet he’s sharp and competent and likeable and formidable. He lives among the detritus of modernity but is not of it, having seen through the mirage of consumer culture and office jobs. In the midst of his aggressive indifference to social convention he seems driven by purpose, although what that purpose is has yet to be revealed.

NOTE: Fight Club is a dark film, in subject and in cinematography. Much of it happens at night, or in dimly-lit rooms. The city it’s set in is a kind of faceless representation of the modern American conurbation, and I had to look up the in-story location. It’s Wilmington, Delaware. Having lived in Wilmington I can confirm that the film’s blend of modern corporate aesthetic and run-down rustbelt deterioration is quite accurate.

Tyler lives in a dilapidated old grand wooden house in the empty, street-lit warehouse district of the city. He steals cars when he pleases, works odd night jobs, nurtures various anti-social habits and buys almost nothing (although Pitt is often wearing stylish leather or downy jackets and other thrift-store finery, so he must spend some of his time shopping for clothes). In reality a man like Tyler would be a strange and off-putting character, probably suffering from mental illness, but the film makes him a bold and handsome uber-rebel. Upon returning home from one of his interminable business trips the narrator discovers that his apartment has exploded (initially attributed to a gas leak). Lacking any evident friends or family he reaches into his jacket and finds the business card given to him by Tyler, who has a profitable sideline making and selling soap from the human lard from the dumpster of his local liposuction clinic. They meet up at a local bar and have an easy rapport, despite living very different lives, as if they are two halves of a whole. It is at this bar that Tyler lays out his vision of society, and it is here that they have their first fight, and it is here that Project Mayhem truly begins.

Tyler vocalizes the film’s ideology:

“Why do guys like you and me know what a duvet is? Is this essential to our survival, in the hunter-gatherer sense of the word? No. What are we then?

We are consumers. We're the by-products of a lifestyle obsession.

Fuck off with your sofa units and string green stripe patterns, I say never be complete, I say stop being perfect, I say let... lets evolve, let the chips fall where they may…

The things you own end up owning you.”

As an answer to the emptiness of modern life Durden proposes a radical kind of existentialism, full of masculine purpose, discomfort, collective drive, and violence. Durden impulsively asks the narrator to hit him, as hard as he can, as they leave the bar on their first night together. So begins Fight Club.

Fight Club grows week by week and becomes a place of bonding and release for men who feel lost in life. Without apparent hierarchy or conversation or social validation the men meet up every Saturday night and take turns fighting, two at a time, until there’s a knock-out or a submission. All comers enter with a presumption of perfect equality and each fighter is only as good as they are. There is no coddling or rank or profit or equity in Fight Club. If it’s your first night there, you have to fight.

The movie veers off as the plot progresses, and develops a strange (of course) love affair with Marla, the progressive abandonment of normal conformity by the narrator and, eventually, the establishment of a paramilitary organization devoted to the nihilistic erosion of the modern world. The film ends as this group (‘Project Mayhem’) uses explosives to collapse five downtown office buildings which headquarter the credit card companies. Before this explosive ending we find out that the narrator and Durden are actually the same person, that the narrator (who remains unnamed throughout the entire movie) invented the personality of Durden to free himself from the strictures of his life: “I am free in all the ways that you are not.”

Themes

The entire film serves as a dark and twisted expose of the alienating effects of modern society on men. Men “work jobs [we] hate so we can buy shit we don’t need.” We end up aimless, alone, emasculated… but harmless. The narrator, before the genesis of his Tyler Durden Jungian shadow figure, is the perfect figure for modern society. He works busily, he travels, he’s quiet and inoffensive, he spends all of his disposable income on consumer products, and he doesn’t question society or cause problems.

Tyler, on the other hand, is a problem for modernity. Leaving aside his antisocial and puerile impulses he is aggressive, dissatisfied, searching for answers and ready to organize with other men to make social change happen. He is, quite literally, the nightmare of the managerial elites. It is a point which is made only infrequently but is undeniable: if our rulers and our managers and our intelligentsia have to choose between (1) a nation of young men desperately unhappy and salving their existential agony with porn and drugs and cars, dying deaths of despair and (2) a nation of focused and organized young men who are psychologically and emotionally healthier but are actively working towards radical social change, they will choose option 1 every time.

The story masks its pointed thematic message with a glib and weird tone and bizarre character details and situations but it shines through nevertheless: modernity’s hope of fulfillment through office work and shopping and medication is a lie. True actualization lies in pushing yourself to your physical limits, creating bonds with other men, and questioning the nature of society.

The fact that Durden ends the film killed (kind of) and the narrator seems to be pulling back from Durden’s anarchic vision does not negate its message. Perhaps Durden’s uncompromising quest to ‘hit bottom’ (“it’s only after you’ve lost everything that you’re free to do anything”) is also a dead end. The movie is not a political polemic. It is not suggesting a particular ideology or philosophical goal but it does point men toward alternatives. These alternatives are rooted in our biological nature and our evolutionary history.

In the world I see - you are stalking elk through the damp canyon forests around the ruins of Rockefeller Center. You'll wear leather clothes that will last you the rest of your life. You'll climb the wrist-thick kudzu vines that wrap the Sears Tower. And when you look down, you'll see tiny figures pounding corn, laying strips of venison on the empty car pool lane of some abandoned superhighway. -Tyler Durden, Fight Club (1999)

Durden’s Fight Club could be seen as a continuation of the long cultural history of ‘rites of passage’ - difficult and dangerous trials which boys had to pass through in cultures all over the world and throughout history in order to become recognized as men. Our civilization lacks rites of passage. Indeed, for many it lacks the formative experiences which bracket and define adulthood.

Google something about ‘manhood must be earned’ and your first several pages of results will be condescending and cautious studies, articles, and opinions from people who do not seem to understand the value of the ethic. In many ways people like that have built our society… but they can’t protect it. Their instinct for safety and consensus and gentle living make them constitutionally incapable of facing the violence of reality. As long as we have a civilization there will be a place for them, but we can’t delude ourselves into thinking that their impulses are scientific or objective. They are emotional reflexes and they necessarily deny much of what we know about human nature and reality. People like this demand protection by institutions… but those institutions eventually require violent young men to act, or they are worthless. Denying this fact is a mistake that no one would have or could have made until perhaps the past few decades. It is shocking how quickly it has spread.

Nietzsche

Like Fight Club, the writings of Fredrich Nietzsche have an enduring appeal for young men. This hilarious scene from Little Miss Sunshine is one fictional example:

My favorite comment below that video is that the young man’s vow of silence is “Rare, most people read Nietzsche and then never shut up about it!” Anyway, Nietzsche’s works parallel Fight Club so closely that the film can be interpreted as a derivation and application of his ideas.

Nietzsche was a deep and promiscuous thinker who abhorred the systemizing impulse of many great Western philosophers and instead wrote in bursts of isolated profundity. Most of his writings are simply collections of aphorisms, organized thematically. It’s quite incredible how much of our modern pathologies were predicted by Nietzsche (a topic for another day) but Nietzsche’s most urgent and lasting idea is the ubermensch, (‘over-man’) a kind of transgressive figure who will move progress and humanity forward through his rejection of convention and morality and the herd.

"I teach you the overman. Man is something that shall be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?… I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star,” he wrote "The overman...Who has organized the chaos of his passions, given style to his character, and become creative. Aware of life's terrors, he affirms life without resentment."

Tyler Durden has abandoned the expectations and norms of modernity and embarked on a quest to strengthen himself by shedding the drives for status and comfort and acquisition. As the story progresses he begins to teach those around him (the narrator, the men of Fight Club, convenience store clerks) the value of living for today, exploring the generative aspects of chaos and violence and destruction.

Tyler Durden never said the following (Nietzsche did), but it sounds like him: "Become who you are!"

If I’m right there are deep biological drives within men and humans generally which require routes of expression. They cannot be erased, only channeled. The innate drives of men are being denied, suppressed, and stigmatized, and a new ideal for the adult male has been cobbled together. It’s too ridiculous and distasteful to be portrayed fully and honestly but it finds its way into films and stories and advertisements and it is the model after which many people deeply hope men will form themselves: shopping, chatting, soft creatures; emotional and agreeable and self-deprecating allies and friends without any hint of strength or aggression or inner character or stoicism; ‘men’ who do not assert, do not dominate, do not threaten, do not fight, and do not grow. I do not think that most men can be fit into this mold, but that doesn’t mean that society is not desperately trying to shove them in, starting in boyhood. It will not work, and if it does it will be followed swiftly by our collective defeat and extinction at the hands of stronger men. Such is nature.

Do you think that at any other time in history, men would accept the thinly vailed discrimination deployed against them by DEI? White male CEO's hiring or promoting women and minorities to positions of power by virtue of their race or gender. Once in power, they would feel justified in shutting white males out.

I distinctly remember reading Chuck Palahniuk's book poolside in Hawaii in the late 1990s. It had that glass chewing style that pinned me to the lounge chair, downing maitais like they were fruit punch. I'd look up and wonder where the fuck I was.