The Lie of The Unconstrained Vision

Interrogating a fertile garden of political and ethical errors

I was going to write about trade-offs today… and then I realized that the lack of acknowledged trade-offs in our political conversations are often part of a larger issue: the triumph of ideals and theory and rigid assumptions over reality and history.

Thomas Sowell writes about the constrained vision versus the unconstrained. The former takes evil and suffering as inescapable aspects of human life and recognizes the complexity and challenge of improvement. The constrained thinker is respectful of tradition and norms and the power of a single individual to remake his or her life and improve the world. The unconstrained thinker (Sarte, Rousseau, Marx, Marcuse, Davis and the rest of the Critical Theorists) believe they have access to deeper truths about humanity (usually relating to its malleability and the primacy of power) and believe that their plans will yield a kind of utopia, provided they are given power and provided that those who oppose them are destroyed or neutered.

One person looks at poor academic achievement in public schools and concludes that better teachers are required, and more motivation among the students, and more discipline and better study habits. A different person looks at poor academic achievement and concludes that the entire system (a poorly defined concept during the best of times, but one which can include metrics and rewards and rules and even language and values) is flawed. Dismantle the system, they say. Decolonize education. Do that, and EVERY child will become an academic superstar (they rarely say this explicitly, for explicit claims are like kryptonite to the person of this second type, but that is what they believe).

One person looks at the varied and unequal distribution of different groups and traits across different organizations and leadership roles and occupations and says: good. Different kids of people will choose to do different kinds of things at different levels of ability. The inequality of opportunity in our society should be addressed by increasing opportunity at the bottom end, i.e., increasing the quality of education and the funds for scholarships and work-training for poor kids and the integrity of poor families. Education should be the paramount value and, after that, frugality and personal responsibility and honesty. A different person scoffs at this kind of old-fashioned rhetoric and diagnoses systemic ills. The problems are so grand and systemic that they cannot be meaningfully addressed by focusing on the lives and choices of individuals and, in fact, those individuals are themselves simply unwitting pawns of the machinery, bereft of agency or honor. Only the vanguard - the educated and privileged overseers - can see the deep problems and only they have a plan to fix them all (learned in college, usually). All they need is power.

One person looks at a rash of gun violence and shoplifting in a neighborhood and concludes that more and better-trained police are necessary. While social causes are extant they can’t absolve people who choose to wound and kill their fellows, and they can’t be allowed to run struggling stores out of poor neighborhoods (destroying precious capital and jobs and stability) so that drug addicts can make a living re-selling stolen deodorant and disposable razors. Increase the disincentives for bad behavior and the behavior will lessen, and then the other institutions in the area (Americorps, after-school programs, small businesses, corporate pharmacies, outpatient clinics) won’t have to bear the varied and heavy costs of disorder and violence. A different person looks at a rash of gun violence and shoplifting and concludes that the system (again) is responsible, that the fault lies not with laws and policies and their attendant behaviors but with more nebulous (and ineradicable) factors: the profit motive, individualism, systemic racism. We can’t address shootings and theft (not ethically, anyway) according to this second person. The idea that people respond to punishment and that communities benefit from law and order are, themselves, oppressive constructs.

There are a few deficiencies in the second person described in each of these hypothetical scenarios:

privilege - people who take these approaches are rarely (in my experience) of the groups they’re trying to help. THEY have never been homeless or a failing student from a broken home or an urban soldier hunting for opponents. They have simplistic and academic understandings of human nature which are often counter-intuitive and unscientific, removing any sense of the power of decisions or direction in a person’s life. They take a paternal and managerial approach to social problems and are undeterred by failure or contrary data. After all… there is always a system to dismantle and the social problems in question can ALWAYS be reduced to its impersonal operation. Which brings me right along to…

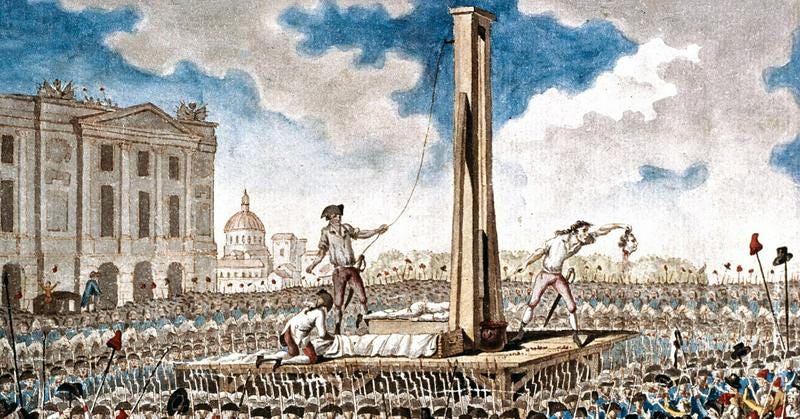

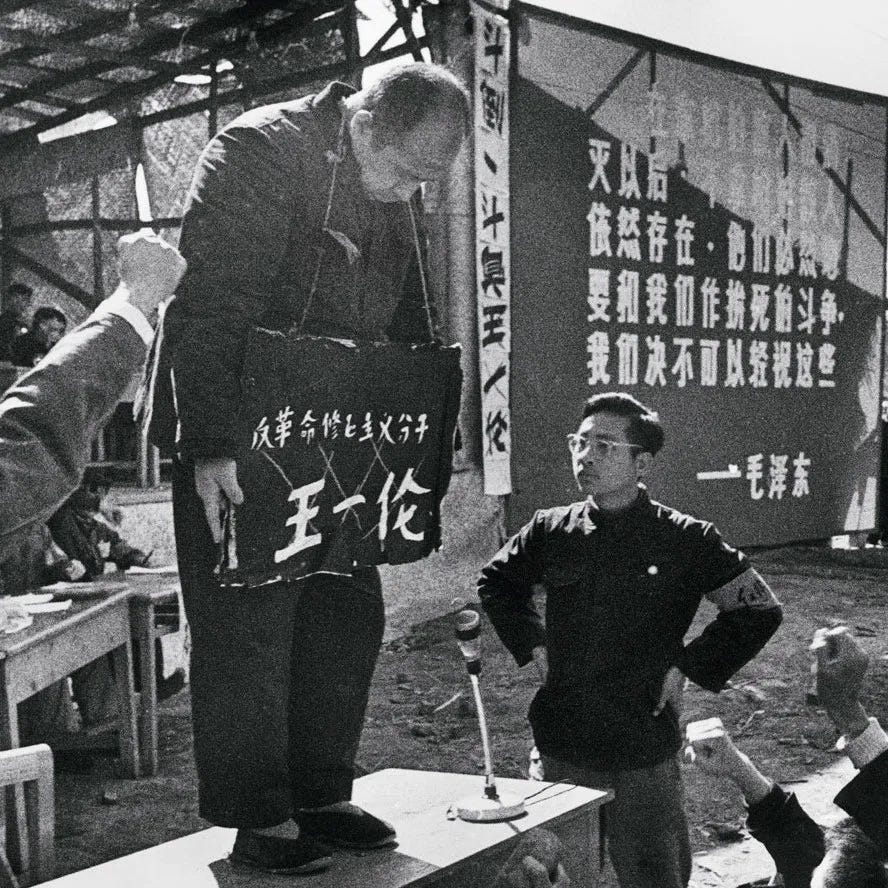

arrogance - is an implicit trait required to think that YOU have the insight and wisdom required to remake society into a utopia. For a century we have seen smart and well-meaning technicians and intellectuals try to manage modern society and, in nearly every case, they fail or generate unforeseen negative externalities. The Bolsheviks believed that they could scientifically manage the economy of the Soviet Union. Critical Theorists believed that they could wipe away every trace of the old and replace it with a kind of egalitarian utopia. The American liberal reformers of the 1960’s and 1970’s sincerely believed they could engineer a ‘Great Society’ to address urban (especially) and rural pathologies and use the state to redistribute wealth and opportunity to artificially engineer a new, progressive middle class. The 1950’s CCP thought they could remake the Chinese economy into a locally-scaled communist post-scarcity economic powerhouse. Tens of millions of deaths from starvation later their enthusiasm was barely dimmed. In every one of these instances (and every similar one) the efforts of the true believers led to far greater suffering and dysfunction. In many cases we’re still untangling and trying to solve them, and new brilliant plans popping up every week in the halls of thinktanks and government and universities are certainly not helping. Society is complicated. If it seems simple to you, and if ALL of its problems seem obvious to you then you are the last person who should be given power to remake it. Their mistakes never reduce the fervor for more and more radical measures, for the exercise of power becomes its own aim and this eventually crowds out the well-meaning and naïve, leaving only the nakedly acquisitive and the brutal.

distance - is similar to privilege but leads to its own challenges. People intuitively believe that they have powers of choice and self-improvement. Without this sense they risk depression and apathy. Yet the reformers often remove those abilities from the groups they’re trying to help, in their universalist schemes. This is rarely explicit (for it’s impossible to verbalize such things without sounding patronizing and, frankly, insane) but the idea that the poor can improve their station by saving money and working hard or the struggling can overcome through effort are regarded as ludicrous. As I’ve written elsewhere, personal effort cannot overcome every collective barrier and there are systemic variables which are sometimes at play. Anyone who discounts the power of the individual entirely though has elevated themselves above those they would help. I’ve chosen my course and educated myself and made my life, they imply, but these people cannot. They need me to be empowered in order to remake society for them. These kinds of condescensions don’t arise regarding people that one is in regular and equal contact with (unless one is a malignant narcissist). They only bloom when one is regarding an entire group or type as an abstract category, for which people cannot feel any true love or concern.

power-hunger - is where we come to the central flaw of the unconstrained visionary. They are using their criticism of their society and their ostensible wishes for the betterment of one group or another as platforms and weapons which they use to gain power and status for themselves. They will use it to the good of all, they claim, (and often believe) but the habits of thought which arise to generate this cast of mind are proud and absolute. They often come to wish the destruction of others who are sincerely trying to help those same groups (with more kindness and realism and less remove), simply because they sense threats to their own power. They come to confuse the improvement of society with the empowerment of themselves and their organizations. This way lies megalomania.