The Nagging Question... of 'American History X'

A minor line in an old film contains wisdom more relevant than ever

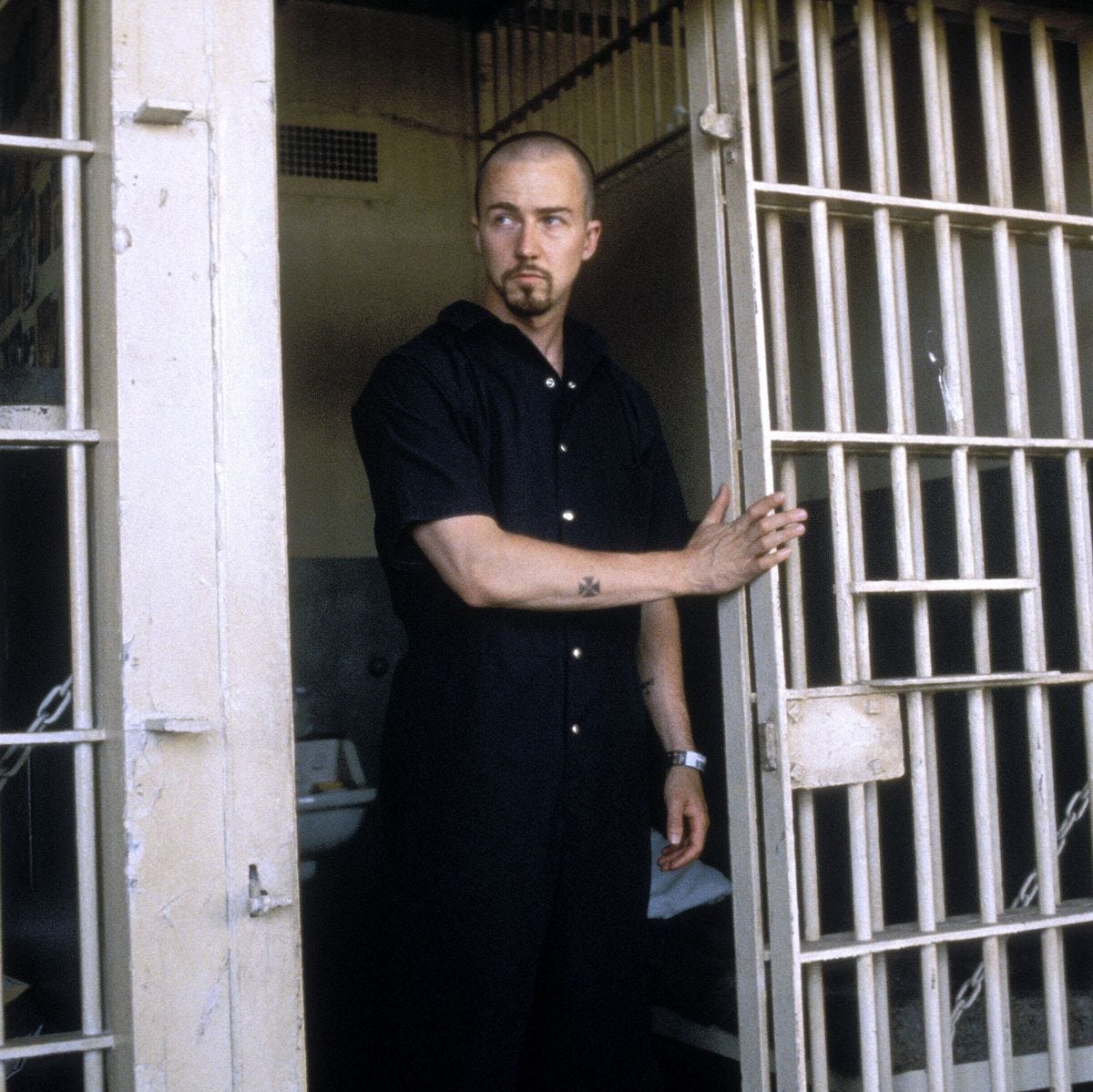

American History X is a great film. I would say that this is an objective fact but I simply don’t know much enough about cinema to comment on its quality as a film with certainty. (As an aside, I’ve recently become fascinated by combinatorial mathematics and cinematic techniques, and for the latter interest I can’t recommend Thomas Flight’s YouTube channel highly enough). What I can say with adequate expertise is that it is a beautifully and tightly-written film with devastating character development, two main subplots which intertwine masterfully, and an ending which cauterizes the open wounds inflicted by the film and leaves a psychic scar of social reflection that should be lifelong. It’s rarely discussed today and I’m not certain if it’s because it’s old, or because its writer and director and actors never made true A-list status (Edward Norton got close) or because it shines a limited, almost sympathetic light on a fictional SoCal skinhead gang. It is nevertheless a film that I feel strongly would profit most adults to view today (please note that it contains sexual scenes and violent scenes and extremely violent sex scenes… they are badly overused these days but for this film recommendation I must issue a trigger warning).

The film tells the story of teenaged Danny Vinyard, a rebellious and uncertain teenager living in one of America’s many liminal spaces: a part of Venice Beach, California, anchored by coastal real estate and solid middle class families which has nevertheless been engulfed by a wave of black gang violence and social disorder. The signs are everywhere around him: at his school and on his walk home. He’s chosen a rather antagonistic image in response: Danny is a skinhead who is deliberately provocative to the black would-be criminals in his school bathroom and on the neighborhood basketball courts.

We see learn through flashbacks (in black and white) and Danny’s narration that his brother was a kind of white power hero to local kids. After trouncing a group of crips in a pick-up basketball game they try to steal a truck that his father gave him, and he shoots one of the thieves and kills another in one of the most eerie and brutal scenes in all cinema.

We see Derek’s time in prison and learn that, while being a kind of racialist fanatic before being sent up, he’s begun to learn the errors of his ways in prison. We come to find out that Danny has been living with the militant, alpha male-image of his skinhead brother for the past two years and striving to become his equal in strength and hate and aggression (and certainty, a trait that seems unbelievably appealing to adolescents) while Derek has turned away from his past and begun trying to mend the gaping hole rent in his life through his own bitter decisions.

There’s a riveting and profound scene where Derek’s English teacher (now Danny’s Principal-a man respected by students and gangbangers and police alike for his experience and education) visits him as he convalesces in the prison infirmary after being raped by his crew, punishment for his prideful disrespect. The teacher discusses the “place [he’s] in” and says that he knows, because he was there too. It’s a place where everyone and everything seems worthy of blame and the anger begins to consume the person… and then he utters his climactic statement:

“I didn’t get no answers because I was asking the wrong questions…”

“Like what?”

“Has anything you’ve done made your life better?”

This is the question that I would pose to the young activists and indignation sowers of today, as an honest query and as a warning. Activism can be worthy and it’s a common undertaking for adolescents, zealous and absolutist as they are. Activism should be guided by older and wiser people, though, and done in the context of a large and hierarchical organization. It must be planned and sober and strategic to have any chance of success. Mindfulness should always be paid to the exact tactical goals of particular actions. There’s generally a conceptual axis, with strategic effectiveness on one end… and emotional satisfaction on another. If you’re doing the thing that feels best and satisfies your indignation then you are not doing effective activism.

Too many movements these days seem based solely upon outgroup hostility and blame, too few accept responsibility for the work of improving communities. Any organization that sells a simple answer to social problems based upon hostility or resentment is almost certainly a waste of time and energy and very probably a path toward dark places. BLM led to the deaths of about a dozen people directly and hundreds or thousands indirectly. It has been exposed as a front for embezzlement and a cynical fraud… and even with all of that I’m grateful, for it could have been far worse. It wasted the money and energy of millions of Americans and stoked nonsensical grievance, based on a willful distortion of reality but it could have been far worse.

Too often activism (like other forms of extremism: cults, substance use, intense hobbies) is so satisfying not because it’s mending the world but because it’s papering over a hole in the activist’s soul. Instead of trying to change the world, try changing yourself first. You will find that it is a much more difficult (but ultimately more rewarding, for you and for the world) endeavor.