I’m not a lawyer, and while I have been following the case and reading dozens of articles, I have no special knowledge of the case. Please keep that in mind.

People can disagree about deductions and interpretations. However, when people (juries) claim a greater degree of confidence than the evidence allows you know that they’re wrong. Even if their conclusions are correct… they simply cannot know this. People have frequently been convicted of murder on the basis of single eyewitnesses, simply because the eyewitness was credible and the defendant unlikeable. In many cases there is actually contrary evidence-in some cases solid alibis! It’s no matter to those jurors. They feel certain, and even when it becomes rather clear in the succeeding years that they convicted innocent people (the West Memphis Three) they react with increased certainty and defensiveness. That’s a psychological defense mechanism. The bottom line is that, while people can disagree about many things you can know that someone is incorrect when they claim certainty about some things. A person who says that they know that their religious affiliation or political stance is the ‘right’ one is wrong, even if the person is right about religion and politics. The claim that they’re wrong is simply a claim about the fallibility and limits of human knowledge and that is a subject on which every person who pays attention to the world is an expert. Remember my point: certain things simply cannot be known beyond a reasonable doubt based on a given set of evidence. It will recur shortly.

There are also cases in which people might not believe that they have certain knowledge which they do not, but are so overcome with hostility towards the defendant that the question of their reasonable doubt becomes irrelevant. Reviewing the evidence of the O.J. Simpson murder trial I cannot avoid the conclusion that many of those jurors were expressing something other than a sincere doubt in the defendant’s guilt with their (not guilty) votes. On the other side of the racial divide, contemplate the many black defendants accused of rape or murder in 1930’s America. In many cases those trials were simply a kind of communal gesture of hatred and vengeance (and racial solidarity).

In neither case (epistemological overreach or motivated reasoning/vengeance) is justice served.

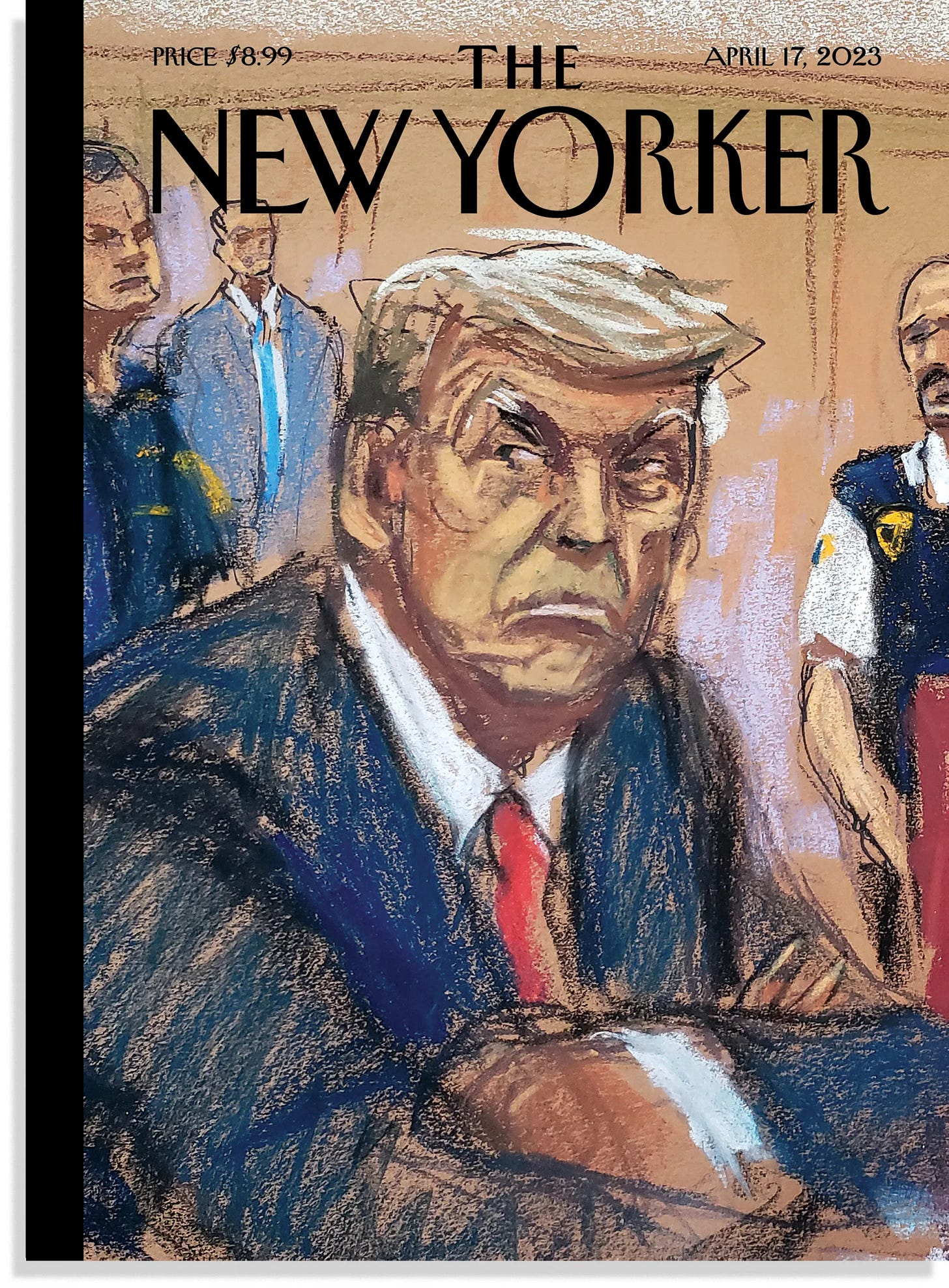

Donald Trump was charged by the Manhattan D.A.’s office with 34 counts of felony falsification of business records. He was just found guilty.

The charges in question relate to payments that Trump apparently made to attorney Michael Cohen, connected to Trump’s effort to pay ‘Stormy Daniels’ before the election to secure her silence. Trump probably regrets that effort at this point, as he should. The falsification charge is only a felony if the falsifications happen in an effort to cover up other crimes.

There are already a number of issues with this case. Why did Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg charge each check/payment as a separate count? What were the other crimes? Why was this case brought in the first place?

The gleeful celebration of the elites will only deepen political and cultural divisions in this country, which is the predictable result of using the criminal justice system to punish opponents

I was in my favorite diner, listening to MSNBC drone on in the background. This was before the verdict had come down so there was none of the gleeful malice that I’m sure has saturated the channel since then. There was still some trepidation… but one point, made again and again and which I found curious, was that ‘the case itself is a win for American justice.’ The idea that even a former president is not above the law is indeed a bracing notion in a republic… but there’s a converse: people should not be prosecuted for essentially political or cultural reasons. D.A.’s are charged with weighing the evidence and acting on behalf of the whole people, which is to say on behalf of justice. The fact that the MSNBC commenters didn’t consider or even address the very real (indeed, overwhelming) likelihood that Trump (not just a former president but a presidential candidate) was being prosecuted as an expression of political and personal animus (or as a cynical political strategy by the entrenched power structure) is telling. People base much of their beliefs upon treasured assumptions and these are never examined, especially when conversing with the ‘in-group’. Questioning the political motivations of Bragg or the reality of racism as a public policy imperative or the feasibility of gender identity will only earn you rebuke and hatred in many groups so people avoid that. Most people even manage to avoid asking themselves the questions. The idea that Trump was guilty of lots of things, therefore any conviction against him is a win for justice, is a tempting ethical shortcut of the kind that deeply appeals to most people, but this is not the standard our criminal justice system aspires to.

The truth is that, the more you dive into this case the more the legal exceptions, evidentiary leaps, shaky assumptions, and weird rationales pile up. Jacob Sullum writes:

"The heart of the case," Bragg says, is Trump's attempt to influence the outcome of the 2016 presidential election by covering up his purported affair with porn star Stormy Daniels. As Bragg sees it, Trump "corrupt[ed] a presidential election" by hiding negative information from voters. Because there is nothing inherently illegal about that, Bragg is relying on a dubious chain of reasoning to charge Trump with felonies under New York law.

Shortly before the 2016 election, Michael Cohen, Trump's lawyer, paid Daniels $130,000 to keep her from talking about the alleged affair. In a 2018 plea agreement, Cohen, who will be the main prosecution witness in Bragg's case against Trump, accepted the Justice Department's characterization of that payment as an illegal campaign contribution. But Trump was never prosecuted for soliciting or accepting that purported contribution. Nor was he prosecuted for later reimbursing Cohen in a series of payments.

There are good reasons for that. The question of whether this arrangement violated federal election law hinges on whether the hush money is properly viewed as a campaign expense or a personal expense. That distinction, in turn, depends on whether Trump was motivated by a desire to promote his election or by a desire to avoid embarrassment and spare his wife's feelings.

Although the former hypothesis is plausible, proving it beyond a reasonable doubt would have been hard, as illustrated by the unsuccessful 2012 prosecution of Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards. The Edwards case, which was based on similar but seemingly stronger facts, foundered on the difficulty of distinguishing between campaign and personal expenditures.

In any event, the statute of limitations for federal election law violations is five years, and Bragg has no authority to prosecute people for such crimes. Bragg instead charged Trump with covering up his reimbursement of Cohen by disguising it as payment for legal services. Trump did that, according to the indictment, through phony invoices, checks, and ledger entries, each of which violated Section 175.05 of the New York Penal Law, which makes falsification of business records "with intent to defraud" a misdemeanor punishable by a maximum fine of $1,000 and/or up to a year in jail.

Under Section 175.10 of the penal code, that offense becomes a Class E felony, punishable by up to four years in prison, when the defendant's "intent to defraud includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof." The indictment, which was unveiled in April 2023, charges Trump with 34 counts under that provision but does not specify "another crime." A month later, Bragg's office suggested four possibilities:

The Federal Election Campaign Act

It is not clear that Trump violated that law, and the Justice Department evidently concluded there was not enough evidence to prosecute him for doing so. Given the fuzziness of the distinction between personal and campaign expenditures, it is plausible that Trump did not think the hush payment was illegal, in which case he did not "knowingly and willfully" violate the statute, as required for a conviction. And if so, it is hard to see how his intent in falsifying business records could have included an intent to conceal a violation of federal campaign finance law.

In any event, it is not clear whether a violation of federal law counts as "another crime" under Section 175.10. In 2022, The New York Times reported that prosecutors working for Bragg's predecessor, Cyrus R. Vance Jr., "concluded that the most promising option for an underlying crime was the federal campaign finance violation to which Mr. Cohen had pleaded guilty." But "the prosecutors ultimately concluded that approach was too risky—a judge might find that falsifying business records could only be a felony if it aided or concealed a New York state crime, not a federal one."

Section 17-152 of the New York Election Law

That provision says "any two or more persons who conspire to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means and which conspiracy is acted upon by one or more of the parties thereto, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor." But as the Times notes, "Federal campaign finance law explicitly states that it overrides—pre-empts, in legal terminology—state election law when it comes to campaign donation limits."

While Vance's prosecutors "briefly mulled using a state election law violation," the Times reported in 2022, they rejected that idea: "Since the presidential race during which the hush-money payment occurred was a federal election, they concluded it was outside the bounds of state law." Even without that complication, the "unlawful means" alleged here again hinges on the doubtful proposition that Trump "knowingly and willfully" violated federal election law.

Sections 1801(a)(3) and 1802 of the New York Tax Law

Section 1801(a)(3) applies to anyone who "knowingly supplies or submits materially false or fraudulent information in connection with any return, audit, investigation, or proceeding." Section 1802 applies to "criminal tax fraud," which includes filing a fraudulent return. According to the statement of facts that accompanied Trump's indictment, he and Cohen "took steps that mischaracterized, for tax purposes, the true nature of the payments made in furtherance of the scheme." How so?

Trump allegedly paid Cohen a total of $420,000, which included the $130,000 hush money reimbursement and "a $50,000 payment for another expense." Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg "then doubled that amount to $360,000 so that [Cohen] could characterize the payment as income on his tax returns, instead of a reimbursement, and [Cohen] would be left with $180,000 after paying approximately 50% in income taxes."

If Cohen mischaracterized a reimbursement as income on state or city tax forms, that would be a peculiar sort of fraud, since the effect would be to increase his tax liability. This theory of "another crime" requires jurors to accept the proposition that tax fraud can entail paying the government more than was actually owed.

Sections 175.05 and 175.10 of the New York Penal Law

These are the same provisions that Trump allegedly violated by mischaracterizing his payments to Cohen. This theory presumably would require additional violations of the law against falsifying business records that the 34 counts listed in the indictment either facilitated or helped conceal. It is not clear what those might be, but we may find out during the trial, assuming Bragg actually relies on these provisions for "another crime."

Slate legal writer Mark Joseph Stern, who initially was "highly skeptical" of Bragg's case against Trump, says he is "now fully onboard." But Stern's reasoning seems to have less to do with the legal merits of the case than with the sense that this could be the last opportunity to stop Trump from reoccupying the White House.

"Obviously," Stern writes, "Trump's criminality during and after the 2020 election, including his work to overturn the outcome through an insurrection, is more serious than the Stormy Daniels payout. Much more serious; no debate there. It would be ideal if Trump faced trial for these alleged offenses first, because they marked a historic and devastating assault on democracy, culminating in an act of shocking violence. He deserves to be held accountable for these actions in open court, by a jury of his peers, before he has another chance to stage a coup. But thanks to Trump's persistent efforts to run out the clock—too often indulged by SCOTUS—it's now almost inconceivable that he will face such a trial before it's time to vote again. What's left, then, is this case."

Stern argues that Bragg's case, like the federal election interference case, is fundamentally "about elections: specifically, who has to follow the rules, and who gets to flout them." In paying off Daniels, he says, Trump acted on his "bedrock belief" that "he need not follow the rules that govern everybody else." But whether Trump actually broke those rules is a matter of serious dispute, the relevant statute of limitations has expired, and Bragg in any event does not have the authority to enforce federal campaign finance regulations.

After taking a long, hard look at potential state charges against Trump stemming from the payment to Daniels, Vance concluded they were too iffy to pursue. Now Bragg is desperately looking for a legal pretext to punish what he takes to be the essence of Trump's crime: keeping from voters information they might have deemed relevant in choosing between him and Hillary Clinton. But that is not a crime, and treating it as 34 felonies stretches the bounds of credulity as well as the bounds of the law.

The prosecution’s case hinged on some very shaky points: first, the account provided by Michael Cohen would have to be accepted at more or less face value (not regarding the payouts but regarding conversations with Trump). Secondly, for Trump to be convicted under NY state law his falsifications would have to be knowing. He would have had to known he was violating the law… and this simply strains credulity. Most people have never heard of a prosecution on charges like these and even most lawyers would not be able to explain exactly what is legal or illegal in this area (as, indeed, it seems that Bragg was unable to). During the prosecution’s closing arguments they focused on the effort to sway the election, which is probably the most psychological salient angle for many voters but is not a crime. Judge Merchan (presiding) helpfully left this fact (the need for intent) out and instructed the jurors that they did not have to agree about which laws were in the effort of being concealed. Judge’s instructions are often the achilles heel of the prosecution when cases are reviewed on appeal but I don’t think that’s relevant in this case. Even if Trump wins on appeal (which I imagine is likely) the damage is done. This trial was never about holding a defendant to a minimal legal standard. The verdict is purely instrumental, which is a clear indication that the cause of the trail was not the demands of justice.

If you read the indictment and the accompanying statement of facts, you will notice a glaring chronological problem with that account: The criminal conduct that Bragg alleges all happened after the 2016 election. Since Trump was already president, ensuring that outcome could not have been his motive.

Beginning in February 2017, the indictment says, Trump reimbursed Cohen for the hush money with a series of checks, which he disguised as payment for legal services. The indictment counts each of those checks, along with each of the corresponding invoices and ledger entries, as a distinct violation of a state law that makes falsification of business records "with intent to defraud" a misdemeanor.

Since all of this happened after Trump was elected, it is clearly not true that the allegedly phony records "conceal[ed] damaging information…from American voters" in 2016 or that the "falsification of business records" was aimed at "keeping information away from the electorate," thereby helping Trump defeat Hillary Clinton. Eisen concedes this temporal difficulty:

Election interference skeptics contend the charges here are for document falsification by the Trump organization in 2017, after the 2016 election concluded, to hide what happened the year before from being revealed. How can we call this an election interference trial, they ask, if the election was already over when the 34 alleged document falsification crimes occurred?

Those skeptics, Eisen says, overlook the fact that "the payment to Daniels was itself allegedly illegal under federal and state law" and "was plainly intended to influence the 2016 election." Although Cohen "was limited by law to $2,700 in contributions to the campaign," Eisen writes, "he transferred $130,000 to benefit the campaign, allegedly at Trump's direction. That is why Cohen pleaded guilty to federal campaign finance violations (in addition to other offenses), for which he was incarcerated. And no one can seriously dispute that the reason he and Trump allegedly hatched the scheme was to deprive voters of information that could have changed the outcome of an extremely close election."

Eisen glosses over the difficulty of distinguishing between personal and campaign expenditures in this context, which is crucial in proving a violation of federal campaign finance regulations. That difficulty helps explain why the Justice Department never prosecuted Trump for allegedly directing Cohen to make an excessive campaign contribution. Contrary to what Eisen says, there is a serious dispute about whether Trump "knowingly and willfully" violated federal election law.

In any case, it is too late to prosecute that alleged crime. And even if it weren't, Bragg would have no authority to enforce federal law.

Falsification of business records can be treated as a felony only if the defendant's "intent to defraud includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof." Bragg has mentioned a violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act as one possible candidate for "another crime." But it is plausible that Trump did not think paying off Daniels was illegal. If so, it is hard to see how his falsification of business records could have been aimed at concealing "another crime," even assuming that phrase includes violations of federal law, which also is not clear.

The legality of the hush payment is uncertain because it turns on whether Trump was trying to promote his election or trying to avoid personal embarrassment and spare his wife's feelings. The same ambiguity poses a challenge for Bragg in trying to convict Trump of felonies rather than misdemeanors: Did he falsify business records to cover up another crime or simply to keep his wife in the dark?

To have been found guilty according to valid reasoning the jurors would have had to believe, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Trump falsified these records, knew he was breaking the law, and did it intending to cover up another crime. If he was simply trying to hide things from his wife: not a crime. If he was trying to sway voters: also not a crime (if so, which crime?). What exactly that crime was supposed to be has helpfully been left vague by the prosecution which is, to put it very generously, unusual.

I do not believe that these jurors could legitimately support the claim that Trump falsified business records in the service of concealing another crime beyond a reasonable doubt. Rather, I suspect that many of the jurors held personal distaste or even hostility towards Trump and that there was a great deal of pressure to conform and do the ‘right’ thing according to the values of the juror’s social set (as we saw with the Harvey Weinstein and Derek Chauvin and Bill Cosby… perhaps if Kyle Rittenhouse had been tried in Manhattan the trail would have had a different outcome). Alvin Bragg may not be a very good legal mind and he’s certainly a cynical man, but his one brilliant move was to bring charges against Trump in Manhattan. Any charges would have done, really. Unfortunately that is not how justice works.

This kind of tribalism and the sense that victory and power are more important than merit and fairness are the great affliction of our society. We used to understand that, despite differences of value or identity, a system that prioritized logic and impartial administration (to some extent) was the best social order available. We now have too many wealthy, powerful, smart people who believe (or behave as if they believe) that there are certain values more important than that impartiality: racial justice, uplifting certain groups, serving other personal political goals, and punishing one’s opponents. God help us.

Falsifying business records is the third-order crime in service of the second-order NY state crime of conspiring to promote the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency by first-order unlawful means.

“What exactly those ‘unlawful means’ were in this case was up to the jury to decide. Prosecutors put forth three areas that they could consider: a violation of federal campaign finance laws, falsification of other business records or a violation of tax laws.” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-charges-conviction-guilty-verdict/

That appears to be the actual structure of the case. Where's the problem, in your view? Surely you don't think this was all done ONLY to protect Melania's virgin ears...

James, beautifully written and thoughtful as ever. This case MUST go before SCOTUS - whether or not they want to get involved is inconsequential. The charges against Trump still remain undisclosed, or at the very least, baffling. More to the point, Trump was NEVER informed of the charges against him - so if the nine justices don't weigh in, the Constitution, its import and meaning, fly right out the window and it's over - but karma is one BITCH and I say, what goes around.... Make it a GREAT weekend, James and know how much your many admirers hold your character and your capabilites in very high esteem - with yours truly at the very top of the list - Be well and keep in touch! Regards from the war zone AKA NYC - John