Class Lessons

Delivered to Middle School Civics Students

Examples of the instruction I’m giving to my students

I recently began teaching at a lower-income school in southern Florida. It’s an interesting environment, offering plenty to write about (and little time to write!). I teach a Civics class to about 80 students (in 3 classes: 20 / 30 / 30 students) and a Research class, where I’m basically allowed to introduce any content I please. So far we’ve covered AI, prompt engineering, scientific notation, logical fallacies, and APA citation formats. Most of my students are in both classes, so in total I instruct a little more than 100 pupils in 6 classes, taught each day.

In my Civics class I obviously include a great deal of American history. When I deliver my lessons, I try to give my students a sense of the feelings and beliefs of the people at the time, to help them understand that the Founding Fathers and the pilgrims and the Native Americans were people just like them, with the same kinds of petty concerns and vanities and longings. Here are some lessons (in slightly more advanced language) that I have delivered to my class:

On The New World

“Imagine that you’re a struggling farmer or shopboy in 18th-century England. You can’t own land (it’s all taken), you can’t marry who who like, you can’t attend college. You can’t read. You might never travel more than 30 miles from the spot that you were born, and there’s absolutely no opportunity to transcend any of these barriers.

Suddenly word gets back to you: there’s a new land, just discovered. It would be as if a new planet drifted into Earth’s orbit today, a paradise full of easy wealth and promise. Except that you know nothing about it. You hear rumors, but not only have you never been there - no one you know has ever been there. No one ever comes back. Nevertheless, if you’re bold and energetic and maybe a bit crazy you might decide to leave everything. You will leave England, and all of your friends and family, forever.

The people who made that voyage were young and brilliant or desperate or odd - mavericks and religious zealots and courageous young men, looking for adventure.

You arrange to work under some anonymous landowner in the colonies for seven years, unpaid. First you must make the trip. You board a ship (not much bigger than this classroom) and you stay within it for two months. If you survive, a new life possibly awaits you.

The Atlantic ocean served as a great filter, mostly only allowing the young and healthy and bold and enterprising to pass. The colonists believed so strongly in abstractions like ‘no taxation without representation’ and ‘natural rights’ because they had each literally risked their own lives to get to a new place, where they could manage their own affairs. Immigration these days is much different, and it’s probably impossible for us to imagine a world so unknown, and so free.”

On Presentism

“Who in here thinks that the Founding Fathers were just a bunch of old white men? Who thinks that they were bad, and that it’s foolish to admire them? After all, they were wealthy slave-owners…

This attitude is called ‘presentism.’ It is the application of modern values and ideas onto the people and societies of the past. It is rather selectively applied, usually only being used when discussing American or European history.

The curious fact is that whatever society exists in 200 years will be very different from our own. It will regard our values and ideas as wrong and brutal and unbelievably stupid (n certain ways), just as we regard some of the Founders’ values and ideas as wrong and stupid.

Do you own a smartphone? Smartphones (like EV batteries and solar panel energy storage units and laptops) rely on the extraction of cobalt from the ground. This extraction often occurs in the Congo, where child slaves are used to get the mineral. Knowing this, will you stop using smartphones? After all, we’re directly supporting slavery.

Do you eat meat? Billions of animals every year are tortured to death in industrial agriculture, so that you can consume chicken and beef and pork. Terrible things happen to them, and that doesn’t really bother us.

I eat meat, and I use a smartphone (but not in class!). However, I also try to avoid judging the beliefs of people living in very different societies according to what I believe is right or wrong. Life requires difficult decisions, and people tend to be selfish and shortsighted. I am, you are, everyone is. If you owned slaves in the 18th century, what might you do? Free them, into a society where work was scarce and survival difficult? Sell them to someone else? Or keep them, and treat them well? After all, American slavery (like serfdom in Russia or indentured servitude or the trade of North African pirates or Ottoman slave traders) was just a normal and well-recognized practice, stretching back thousands of years. In some ways it was more brutal, but that doesn’t mean that slave owners were bad people, just as it doesn’t make modern Americans bad people to benefit from cheap agricultural labor or African minerals. People exist within the system they’re born into, and they must try to make the best decisions they can using the norms and beliefs they’re exposed to. It would be a mistake to believe that you, as a modern person, are better than the people in the 18th century, just because you understand that racism and domestic abuse are wrong. Perhaps your ideas are kinder. Perhaps you’re better educated. But you also have an incredibly soft and protected life compared to many of the people of that era. It’s difficult to even imagine what life might have been like for them… but it’s useful to try.”

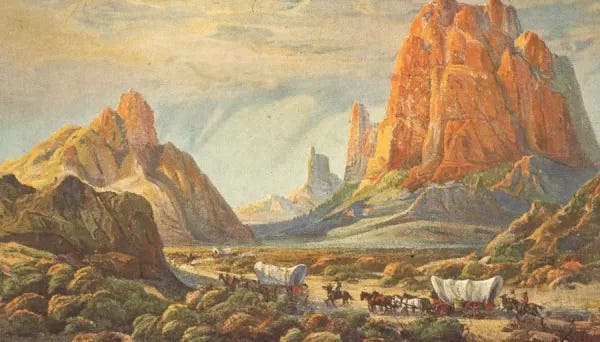

On The Frontier

“You’re a man or woman, with kids and no money. All you want is to own your own farm, and you hear that land is available for the taking out West.

You pack up your meagre belongings, and travel there. Your wife and kids ride on your two horses, and you pull a small wagon with your few pieces of furniture and cutlery. You know very little about the place you’re going (just rumors), but you’re healthy and you’re determined to build something, together.

When you arrive you realize that tribes of people from different cultures have been travelling and hunting across this land for generations, but you don’t see any. You only hear word of attacks on other settlers, far to the North and the South of you.

It never occurs to you that you’ve ‘taken’ anyone’s land. After all, there was no one here. You’ve never seen anyone. But your presence is part of a gradual wave of migration, and the more white people arrive, the more pressure builds on the government to bring in the army to protect your home and your children. A treaty was signed with some of the Native American tribes 50 years ago, but you lived in an entirely different state then and you know nothing about it. The government can’t stop the settlers, and it can’t allow them to be murdered by raiding parties. It sends in the U.S. Army.

This is the story of Westward expansion. Yes, there were lots of atrocities and broken treaties, but mostly it’s just a story of two cultures increasingly overlapping: one full of millions of families who wanted nothing more than their own farm, the other a much smaller group of nomadic hunters who simply wanted things to go back to the way they were.

There’s no going back. There never is, in history. If you want things to stay the same you will always be disappointed, eventually. All you can do is try to make the best decisions about your place and your time. Believe it or not, history is helpful for that. It illustrates the decisions and dilemmas of the past. But we should all understand that history is very complicated. You never have the full picture. If someone is telling you a neat, moral story with clear bad guys and good guys then that person is probably simplifying matters, or they’re lying. Life might be more complicated today but it’s also much more full of information, and order, and comfort.

The life of the American revolutionaries, and the pilgrims, and the settlers, and the Native Americans were full of mystery and danger. Their decisions shaped the civilization we now inhabit, just as yours will shape the civilization of the future.”

I've had similar feelings to yours about what slavery was and wasn't. To grasp this aspect of our past you'll find an understanding in books; never on film, which is the easier propensity for too many.

Presentism, or the uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes is to assume a morally superior stance upon the historical past. And this is, well, kind of stupid. If the stated purpose of viewing the past is to denigrate the voices from that past - what kind of history would we get? The question answers itself.

As for the settlement of the West, not a few of those venturing forth carried with them the Bible as Christians. This meant that the natives were almost unfathomable to them. The utter savagery traded back and forth can't be seen as noble. Only one side could prevail in such a life and death battle in which each side exterminated the other whenever possible. And the truth of this saga isn't for the faint-of-hart, nor is it for children.

I don't think it's reasonable to generalize "no taxation without representation" as a belief founded in the immigrant experience. In the first place, by the time that slogan was popularized, there was already a sizeable native-born population descended from other immigrants. It's the entire reason why the United States defines citizenship by birthright. In the second place, not everyone in the United States at the time believed in seceding from England. Loyalist and revolutionary populations were close to equal in size, with the majority just keeping their head down and waiting to see who won.

There's a similar problem in your depiction of slavery. Not everyone in the United States believed in slavery, even in the South, because it was an economic system that only really benefited the planter class. On one end, you're right that presentism isn't compatible with a coherent civics education, and the decisions people made at the time need to be interpreted in the context of those circumstances.

At the same time, though, you can't pretend as if the decisions these people made were universal or obvious. By all accounts we have, they argued with each other constantly about what the best response was to their material conditions. I don't think it makes any sense to valorize the leaders of the South who happily marched their free population to horrible deaths in an unwinnable war as if they were only acting according to the logic of their time when they only got to this position by bullying or outright murdering other leaders who correctly realized that this stance was unsustainable both politically and economically, if not morally.